The following article is the first piece of a two-part series done by our team and published by the DFRLab. Read more about the developments that shaped #Montenegro as a country, media, and information environment as well as foreign influence it faces today.

During the last two months, the Balkan nation of Montenegro has been rocked by a series of protests sparked by the nation’s adoption of a religious freedom law in December 2019. While the protests themselves are relatively recent, they are the culmination of Montenegro’s long and complex history regarding its relationships with Serbia and Russia. The country has cycled through many systems of government over the centuries; each of them has left a significant influence on the people and the country, including its current media environment.

Located on the Adriatic Coast, Montenegro was home to numerous Slavic tribes, going back more than a thousand years. In the late 15th century, much of it fell under control of the Ottoman Empire, though it maintained a significant amount of autonomy. After a series of 19th century wars with the Ottomans, Montenegro declared independence in 1878. By the early 20th century, it was briefly an independent kingdom until it joined the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. Occupied by Axis powers in World War II, Yugoslav partisans liberated the kingdom, and, in the aftermath of the war, it became part of Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia under the leadership of Josip Broz Tito.

In the 1990s, ethnic tensions and growing calls for independence began to tear up Yugoslavia, leading to regional conflict and war. While Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, and Slovenia went their separate ways, Montenegro remained part of a reconstituted Federal Republic of Yugoslavia along with Serbia. The relationship, however, did not last long: Montenegrin discontent with the union’s system of government and Montenegro’s adoption of euro as a single currency lead to calls for greater autonomy.

In May 2006, Montenegro’s wish to become an independent country with a parliamentary political system came true after the passage of a national referendum. While the country maintains close cultural and religious ties with Serbia, it quickly achieved international recognition, joining the United Nations that same year. This was followed by the opening of negotiating talks with the European Union in 2007 and becoming a NATO member in 2017.

Despite all of these achievements over the last 14 years, Montenegro continues to be subjected to foreign influence, particularly from Serbia and Russia. While this influence takes many forms, it is particularly notable in terms of Montenegro’s information environment.

The internet and media

According to data from the Statistical Office of Montenegro (MONSTAT), Montenegrins use the internet mostly for participating in social networks (84.6 percent), making free online calls (84 percent), reading online newspapers and magazines (75.7 percent), and sending and receiving email (70.5 percent). Meanwhile, January 2020 data from Web analytics firm SimilarWeb shows that six of the top 10 media platforms in the country — Kurir, Blic, Alo, Espreso, Srbija Danas, andPink — originate from Serbia, while only four originate from Montenegro itself: Vijesti, CDM, IN4S, and Umrli.me.

When it comes to social media usage, StatCounter’s data shows that, in the last five years, Facebook has become the platform of choice for Montenegrins (90.1 percent use it), with usage of Instagram (5.71 percent), Twitter (1.64 percent), and YouTube (0.6 percent) significantly behind.

Russian influence in Montenegro’s affairs

Russian influence in Montenegro has deep roots, including a shared Slavic history and affinity with the Orthodox Church. Today, Russia uses these connections to strengthen its influence further through the manipulation of Montenegrin pan-Slavic identity, the power of the church, and economic connections.

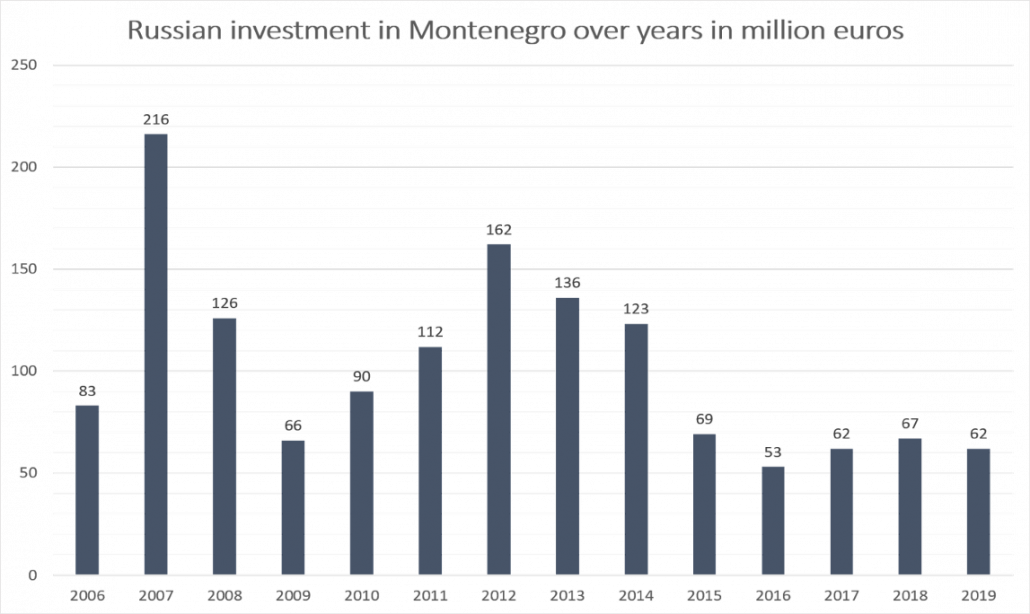

Even before Montenegro’s independence, Russia started to invest through companies and individuals across different sectors, from the metal industry to tourism. According to official registries since Montenegrin independence 14 years ago, Russia has made 1.4 billion euros in direct investments. According to an official request for information from the Atlantic Council of Montenegro to MONSTAT and the Ministry of Interior, there are 1,722 registered companies in Montenegro owned by Russian citizens, with Russians owning around 3,600 properties, including schools and kindergartens, in the town of Budva alone. Data from the Montenegrin Ministry of Interior from 2018, obtained also upon request, shows that some 4,500 citizens of the Russian Federation have either temporary or permanent residence permits in Montenegro

Besides the abovementioned economic influences, Russia has meddled in Montenegrin politics as well. The most glaring example was an attempted coup in October 2016, which appeared to be the work of a Russian-backed opposition coalition in Montenegro — the Democratic Front — and the GRU, according to analysis conducted by Bellingcat and The Insider. Ultimately, the High Court of Montenegro found two Russian citizens, nine Serbian citizens, and three politicians from the Democratic Front guilty of the failed plot.

Throughout Montenegro’s NATO integration process, Russian influence has included diplomatic reactions and media attacks against the government, import bans on Montenegrin state-owned winemaker Plantaže, and a boycott by pro-Russian opposition parties of the 2017 NATO membership ratification vote in parliament.

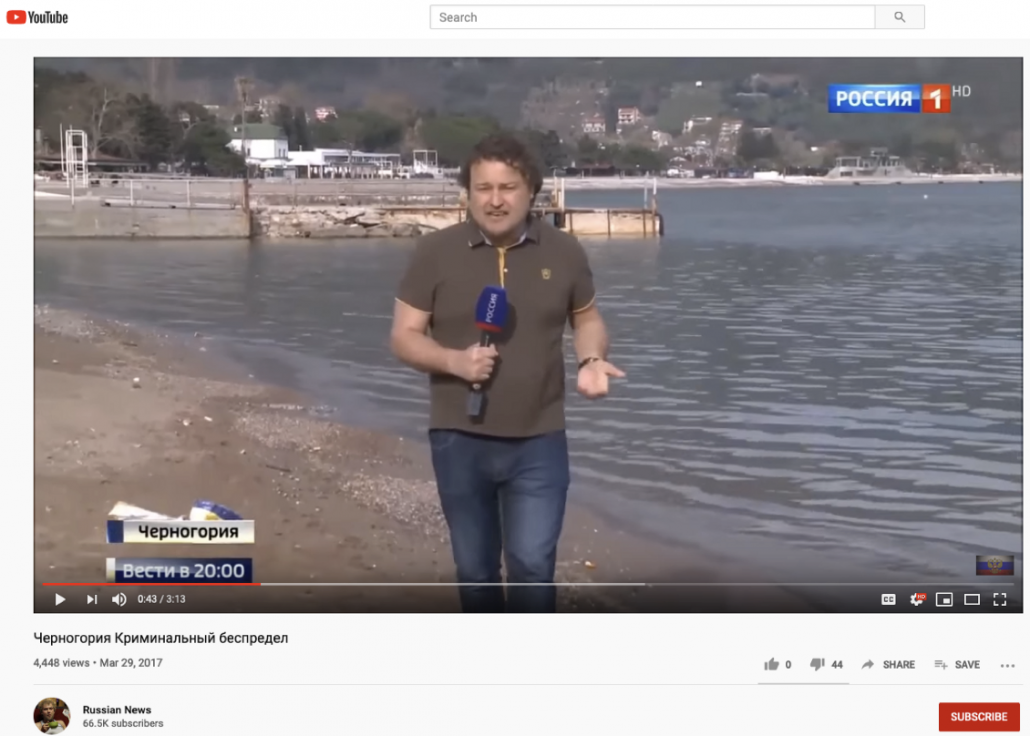

But that was not the end of it. In March 2017, Russian state media outlet Rossiya 1 released a short documentary claiming that Montenegro was “dangerous for Russian tourists, with a high risk of contracting infectious diseases,” as well as “dirty beaches, minefields, and political instability, followed by arrests of Russian citizens for unknown reasons.”

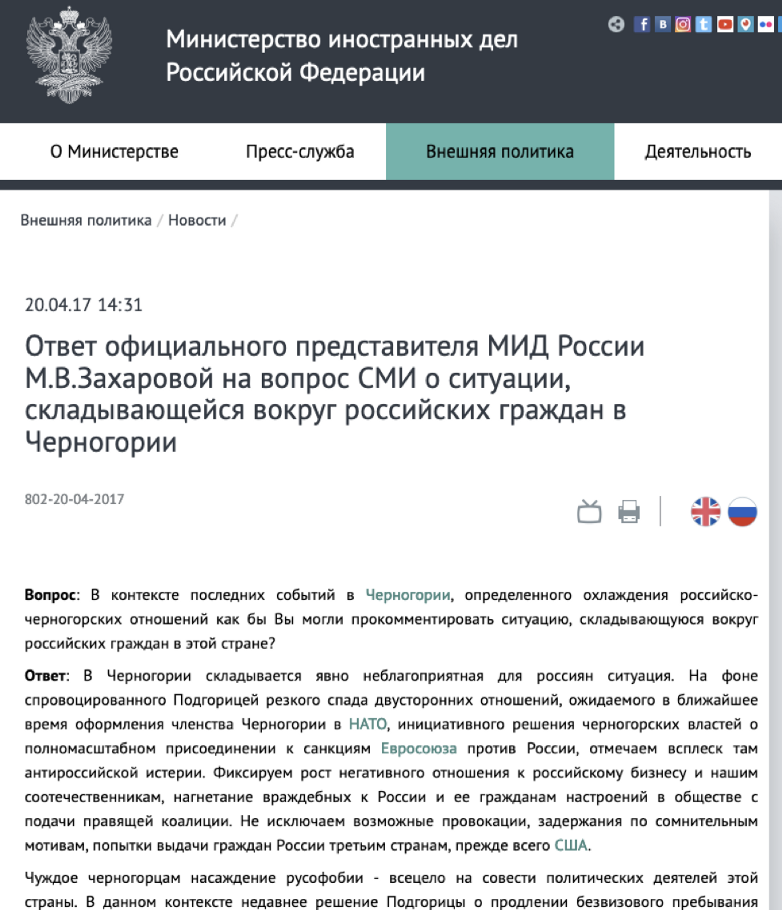

A month later, the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs continued the negative campaign, citing “a surge of anti-Russian hysteria there (Montenegro)” and stating, “We note the growth of a negative attitude towards Russian business and our compatriots. We do not exclude possible provocations, detention for dubious reasons, attempts to extradite Russian citizens to third countries, especially the United States.”

The Russian Federal Tourism Agency used the same line of attack when it urged tour operators to inform customers of the “unfavorable situation” for Russians in Montenegro. Despite these negative narratives on the part of the Russian government, the year ended with more than three million overnight stays in Montenegro by Russian tourists.

Serbian interference

After the dissolution of the State Union of Serbia and Montenegro and the Montenegrin independence that followed, Serbian influence has become more and more apparent. Unlike Russia, Serbia does not have the financial power to influence Montenegro’s overall economy. Instead, it wields its media influence to spread narratives and disinformation, employing bombastic headlines regarding Montenegro’s development as a country. Serbia also exerts its influence through a church in Montenegro: the Metropolitanate of Montenegro and the Littoral, which is the largest eparchy of the Serbian Orthodox Church. Outside of these vectors for influence, the relationship between the two countries is generally cooperative, with ongoing collaboration on many other matters.

When it comes to media influence, pro-Kremlin outlet Sputnik Serbia exerts significant influence in both Serbia and Montenegro. The Digital Forensic Center of the Atlantic Council of Montenegro researched Sputnik Serbia narratives in 2018, with the aim of understanding the outlet’s messaging targeting the Western Balkans countries, the European Union, and NATO. For Montenegro, the center identified 554 articles, most of which focused on ethnicity, historical revisionism, anti-Serbian discrimination, Montenegrin membership in NATO, and the country’s path to join the European Union. Some of the main narratives identified were: “Montenegro and other Western Balkan counties represent a playground of conflicts of interests between East and West” and “NATO is aggressive and incites provocations.”

Like Russians, Serbian tourists visit Montenegro in large numbers. In summer 2019, for example, upwards of 460,000 Serbian tourists visited the country. Because of the tourism industry’s significant importance as a means of national income and the intense Serbian interest in vacationing in the country, the industry is high on the list of targets against which Serbian media spread disinformation, especially in the lead up to the summer season.

Many articles from Serbian outlets cast Montenegro as an expensive and unsafe tourist destination with dirty beaches and aggressive locals, featuring headlines such as: “Tourists massively cancel their vacations in Montenegro” and “Snakes came out from the sea and went after people on the Buljarica beach.” Similar propaganda has been observed in prior years, but so far it has not impacted the number of Serbian visitors or the overall tourism economy.

Looking forward

All of these prior campaigns are to a certain extent insignificant, compared to the one underway now. The Law on Freedom of Religion and Belief, adopted by the Montenegrin Parliament in late December 2019, provided an opportunity for numerous Serbian media outlets to spread different narratives against Montenegro and its people. The likely objective of these campaigns is to polarize society, create tension, and ultimately destabilize the upcoming elections in the country.